Jag sitter och skriver av originalbreven mellan Augusta och hennes mamma. De sista breven. Augusta orkar bara skriva några rader, sedan fyller maken Adolf på med beskrivningar av Augustas sista dagar.

Jag sitter och skriver av originalbreven mellan Augusta och hennes mamma. De sista breven. Augusta orkar bara skriva några rader, sedan fyller maken Adolf på med beskrivningar av Augustas sista dagar.

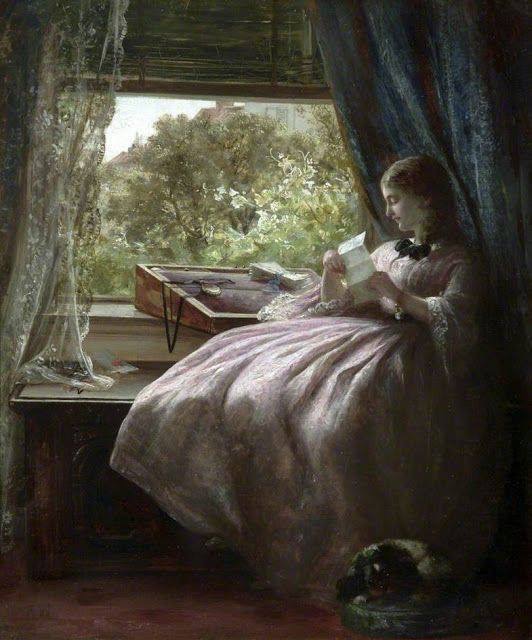

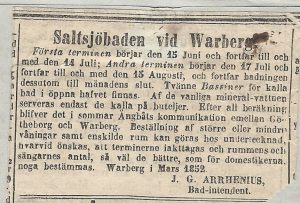

I början av juli 1855 är Augusta så sjuk av sin Tuberkulos att hon och maken Adolf beslutar sig för att åka till Varberg. Kanske hade de redan tidigare bestämt det, badsäsongens bokningar gjordes nog redan på vårkanten. Men det måste varit ett svårt beslut, att när hon var så sjuk, faktiskt lämna sin mamma och sin ettåriga lilla dotter på Loddby. Förmodligen med vetskapen om att hon aldrig skulle återse dem. I brevväxlingen med sin mamma berättar hon om den mödosamma resan, först med häst och vagn till Söderköping och sedan med ångbåt på Göta Kanal till Göteborg. Till en början var det otroligt hett, därefter började det regna. I Göteborg gick ingen ångbåt vidare till Varberg utan de fick hyra en vagn med sufflett. Och det fortsatte bara att regna hela resan. Augusta var så medtagen av resan, speciellt med den skumpande hästskjutsen de sista dagarna.

Augusta:

Warberg d: 6 juli 1855

Älskade Madi!

Af dessa få rader vet Madi att jag är vid lif, men jag är så svag och klen att jag omöjligen kan skrifva mer än några få ord. Adolf min välsignade öfverträffliga make har lofvat med några penndrag säga vår kära gamla Madi hur och när vi kommo hit. Adieu gamla välsignade gumma.

Din tillgifna dotter Augusta.

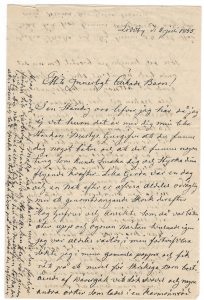

Mamma Anna (Madi):

Loddby d: 11 juli 1855

Mitt Innerligt Älskade Barn

I en ständig oro lefver jag här, då jag ej vet huru det är med dig min lilla stackars martyr. Gud gifve att du funne dig nogot bättre och att det fanns nogonting som kunde smaka dig och styrka dina flyende krafter.

Augusta:

Warberg d: 23 juli 1855

Älskade Madi!

Gud välsigne den doctor Strömqvist! Ty han har räddat mig.

Hälsa Anna och Gerda. Gud bevare barnet. Adieu älskade Madiadi!

Din lydiga dotter Augusta

Tyvärr blev det inte så. Doktor Strömqvist var nog en bra doktor. Han ordinerade stärkande bouillon, men Tuberkulosen kunde inte ens han råda bot för. I brevet beskriver Adolf vidare hur Augusta fått krampanfall och hur doktorn snabbt var på plats för att ordinera frottering av kroppen med kamferliniment.

”Men just under det vi hållo på att äta, mama, så stelnar hon plötsligt och förlorar i ett ögonblick allt medvetande. Knifven släpptes i golvet, gaffeln förblef hårdt quar i handen, hufvudet drogs bakut och en stel kramp höll under ett par minuter kroppen orörlig. Omedelbart derefter armar och ben skakade af våldsamma konvulsiva ryckningar.”

28 juli avled Augusta och vi vet ännu inte om det var av själva Tuberkulosen eller om kramperna orsakades av en tidigare felaktig behandling av sin doktor i Stockholm. De brev som beskriver dessa misstankar är försvunna, men de nämns i efterkommande brev.

Och sorgligt nog fick inte mamma Anna beskedet förrän flera dagar senare. Så när Augusta redan varit död i tre dagar skriver hon ovetandes till Adolf.

Loddby 31 juli 1855

Min älskade Adolf!

… Skulle hon komma sig, är det säkert nödvändigt att akta henne för kall luft, bäst att i sitt fönster inandas sjöluften. Det är visst nyttigt att hvarje afton tvätta henne med ljumt rött vin.Finns ingen möjlighet att åt henne få något verksamt motgift. Med fasa motser jag nästa post. Gud hjälp oss bära så mycken sorg. Lefver den älskade varelsen så gif henne från mig en puss och min välsignelse!

Augusta ligger begravd på Östra kyrkogården i Varberg. Där ligger även doktor Strömqvist!