Idag skriver jag till er som undrar hur man hittar en historia som Anna Stinas, som jag berättade i mitt förra blogginlägg. Och det bara genom att leta i våra öppna svenska arkiv. Det finns nämligen inget skrivet om kusken eller hans hustru Anna Stina i Augustas dagböcker eller brev. Allt kommer från mina efterforskningar på nätet.

Jag tänkte visa hur jag gick till väga, steg för steg. Nästan allt hittar jag på Riksarkivets webb. Jag började med att ställa frågan:

1. Vilka personer dog på gården Loddby under 1840-talet?

Jag söker på Riksarkivet, bouppteckningar och hemorten Loddby.

Så läser jag igenom de bouppteckningar som är digitaliserade. Jag hittar några som jag tycker är intressanta, bland annat Anna Stinas.

- Resultat: Anna Stinas dödsdatum, barnens namn och ålder, makens yrke.

2. Nu går jag vidare för att ta reda på vad hon dog av.

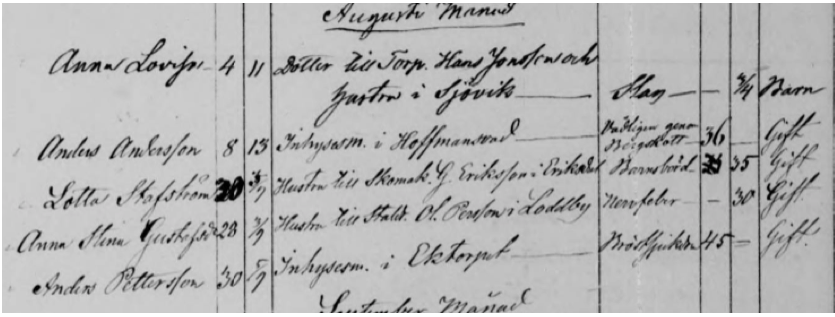

Söker i Kyrkoarkiv, Kvillinge, död och begravningsböcker, 1854

- Resultat: dödsorsak Nervfeber vilket oftast var Tyfus eller kunde även vara Salmonella.

3. Vilka var de, Anna Lisas familj?

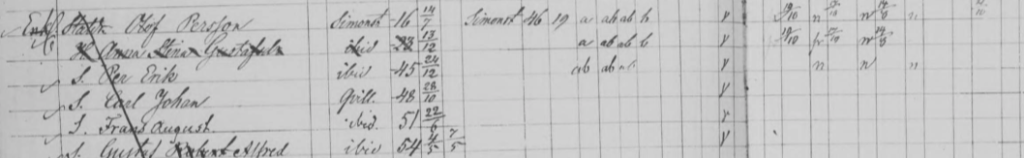

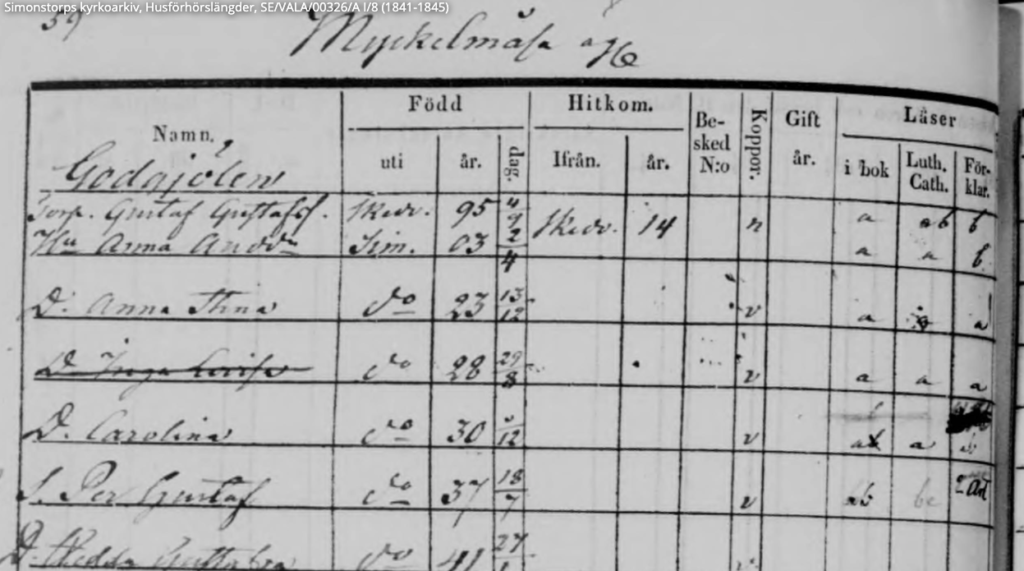

Söker i Kyrkoarkiv, Kvillinge, husförhörslängder 1854 (och omkringliggande år). Bläddrar fram till Loddby (gårdarna finns i bokstavsordning). Här finns alla som var skrivna på Loddby under denna tid.

- Resultat: Var de är födda och när, varifrån de flyttade in och när, hur bra de var på att läsa (bibeln mm) enligt prästen. Här finns även noteringar om vaccinationer! Jag noterar att de är statare.

4. När flyttade de till Loddby?

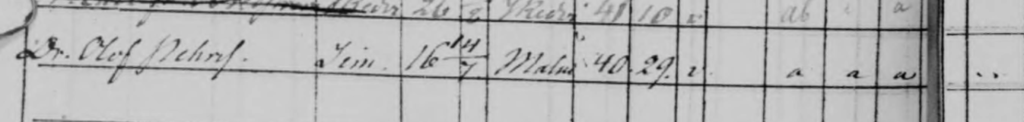

Söker i Kyrkoarkiv, Kvillinge, inflyttningslängder, 1846, för att se när de flyttade in.

- Resultat: September 1846

5. Varifrån flyttade de, från vilken gård?

Söker i Kyrkoarkiv, Simonstorp, utflyttningslängder, 1846 för att se varifrån de flyttade.

- Resultat: Godgölen.

6.Vilken gård och familj kom Anna Lisa från?

Söker i Kyrkoarkiv, Simonstorp, husförhörslängder efter Godgölen, men det är ingen gård och finns inte i registret. Googlar på Godgölen på nätet med olika stavningar och hittar var sjön ligger. Hittar lite länkar till andra släktforskarsidor och hittar så småningom att torpet hör till gården Myckelmåssa. Tillbaka till husförhörslängden och hittar torpet Godgölen under Myckelmåssa.

- Resultat: Anna Stinas familjs data, samt pigor och drängar på torpet. (Döttrarna har bra betyg i läsning!)

Där finns även Olof Persson som dräng.

7. Var finns den lille sonen?

Sonen, född på julafton 1845, finns inte med i husförhörslängden trots att han föddes på Godgölen 1845. Jag går vidare till Kyrkoarkiv, Simonstorp, födelseböcker.

- Resultat: Hittar uppgiften om Per Eriks födelse och att modern var fästekvinnan Anna Stina. Inget skrivet om ”oäkta”.

8. När gifte de sig?

Går till Kyrkoarkiv, Simonstorp, vigsellängder.

Eftersom de står som gifta när de flyttar in på Loddby, måste bröllopet skett mellan Per Eriks födelse 1845 och september 1846. Jag letar igenom vigsellängderna och hittar paret där.

- Resultat: Gifta i februari 1846.

9. Vad händer i den lilla familjen?

Nu följer jag familjen framåt i husförhörslängderna i Kvillinge från 1845 – 1854 och hittar de tre sönernas födelsedatum.

- Resultat: Data på sönerna.

10. Vad händer efter Anna Stinas död?

Jag fortsätter följa familjen i husförhörslängderna 1855 – 1856. Då flyttar änkan och pigan Fredrika Söderström in i familjen. Och 1856 flyttar de från Loddby och Olof slutar som statare och kusk, och blir tegelbruksarbetare. Alla deras förflyttningar inom församlingen finns att läsa i husförhörslängderna under respektive boställe.

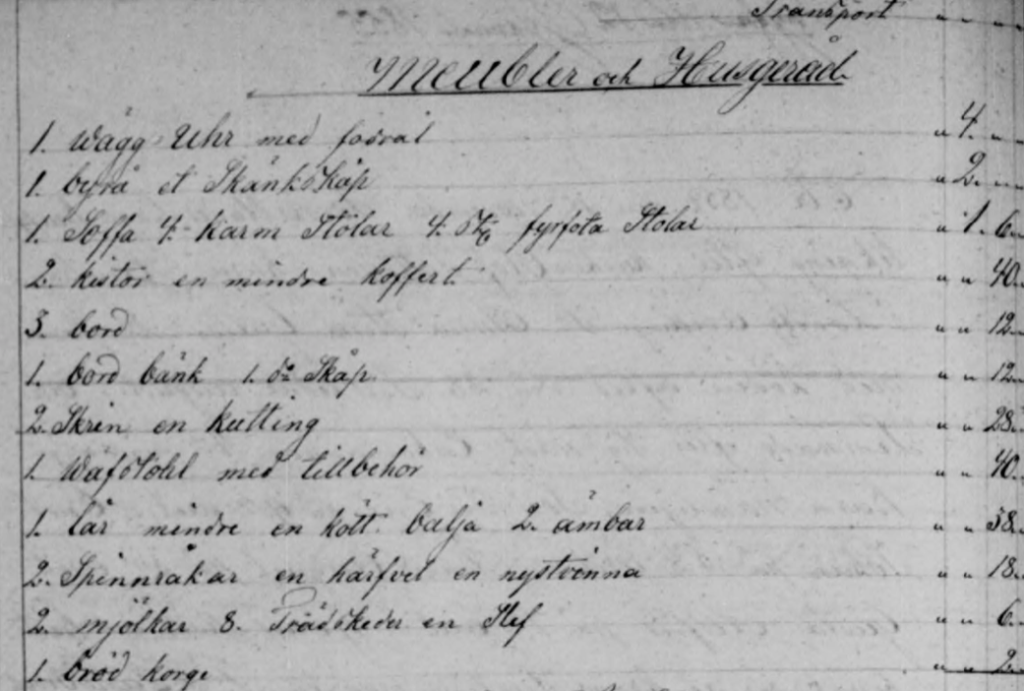

11. Vad kan jag få ut av bouppteckningen?

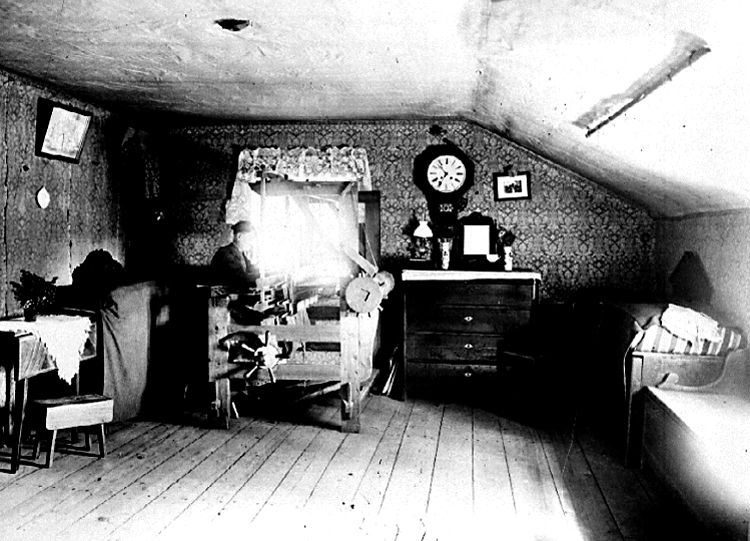

Åter till bouppteckningen. Bouppteckningar kan innehålla så mycket intressant information om hur folk levde och hur deras hem såg ut. Det gäller att läsa mellan raderna och ta reda på vad till exempel det betyder att en statare ägde en vävstol och en hyvelbänk. Vad kan uppsättningen av kläder berätta?

Det här var i alla fall ett smakprov på vad man kan hitta på Riksarkivet. Det är ett ständigt hoppande från det ena registret till det andra, den ena församlingen till den andra. Det tar tid, men är väldigt spännande!

Hoppas du blev lite klokare och kanske lite sugen på att söka din egen historia? Lycka till med dina egna efterforskningar!

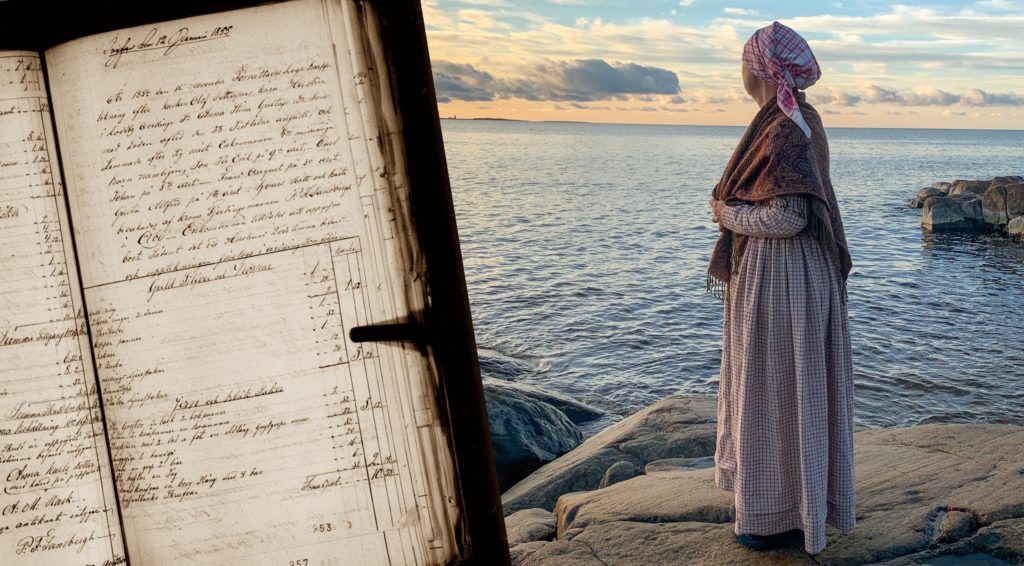

Jag har länge haft ett par gardiner liggande, inköpta på Myrorna. Jag ville absolut sy en klänning som i bästa fall påminner om en statarhustrus sommarklänning. Och förkläde med. Och jag skulle sy dem för hand. De kläder jag hittills sytt har varit för en dam i Augustas samhällsklass, för att känna efter hur det är att leva i sådana kläder. Hur ska jag någonsin kunna göra likadant med min statarklänning? Jag tror aldrig jag skulle klarat av det hårda livet. Men klänningen är nu färdig, förklädet återstår. Jag satt i vår stuga i Österbotten och sydde på kvällarna under fotogenlampans ljus. Min man fotograferade mig på klipporna vid Norra Kvarken. Till sommaren ska jag jobba på landet några dagar i min klänning, för att se hur det känns.

Jag har länge haft ett par gardiner liggande, inköpta på Myrorna. Jag ville absolut sy en klänning som i bästa fall påminner om en statarhustrus sommarklänning. Och förkläde med. Och jag skulle sy dem för hand. De kläder jag hittills sytt har varit för en dam i Augustas samhällsklass, för att känna efter hur det är att leva i sådana kläder. Hur ska jag någonsin kunna göra likadant med min statarklänning? Jag tror aldrig jag skulle klarat av det hårda livet. Men klänningen är nu färdig, förklädet återstår. Jag satt i vår stuga i Österbotten och sydde på kvällarna under fotogenlampans ljus. Min man fotograferade mig på klipporna vid Norra Kvarken. Till sommaren ska jag jobba på landet några dagar i min klänning, för att se hur det känns.